3 foot dog bone

Dog Paw Anatomy, Bones & Evolution

Greys Anatomy is not the only anatomy you should be digging into. If your best friend has four paws, you should know them like the back of your hand. If you think about it, they traverse the world barefoot almost at all times. Stepping on hot concrete, icy pavement, or rocky hill, you name it, is far from comfortable.

However, while people take a great deal of decision-making when picking the proper footwear, they not so often think about their dogs paws well-being. What do your dogs paws consist of, and why are they so resilient against the ever-changing environment? Moreover, how did they even develop?

Anatomy

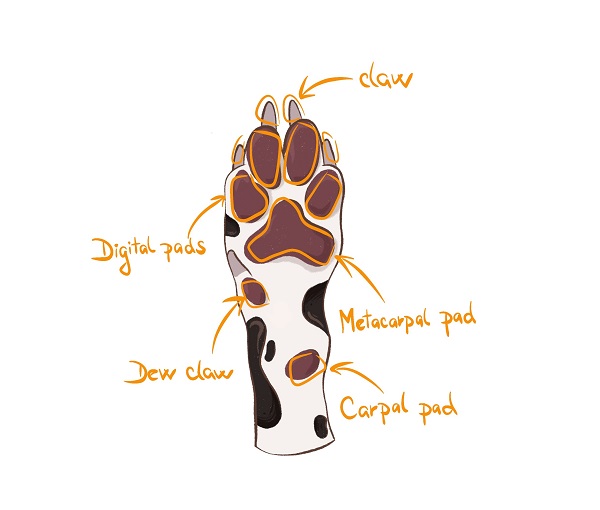

To get a basic understanding of the canine paw, you must know that it essentially consists of 5 parts:

- Claws could be canine equivalent to nails. They are located at the end of the dogs toes and have multiple crucial purposes. They both provide the dog with stability when standing and security by enabling him to defend. Moreover, toenails create traction necessary for digging holes or tearing up their prey.

- Dewclaw, on the other hand, could be considered a dogs thumb. You can find it more to the side and slightly away from the central part of the canine paw. Dewclaw is primarily present in front paws but rarely can appear in rear ones as well. Some breeds as Australian shepherd or rottweiler have double dewclaw; these are then known as polydactyl. It doesnt usually touch the ground; however, dogs running at high speeds use them for extra traction to better stabilize the carpal joint. Some dogs even use it when climbing or holding objects. Dewclaws are not present in all dog breeds and are sometimes removed in puppies to prevent infection. Such procedure is usually taken only if the dewclaw is loosely attached.

- Digital pads are probably the most known part of a canine paw. Dogs have 4 digital pads in total, one at each toe. They are hairless; however, pieces of fur may get in between toes. Digital pad is a thin, pigmented, and keratinized layer of skin covering tissues of collagen and fat. Thanks to the layer of fat underneath the skin, digital pads are shock-absorbing, protecting the canine joints and bones from irritation due to unpredictable or rough terrains. However, the purpose of digital pads goes beyond being the shock absorber. They not only provide a better grip on any surface but also reduce the heat transfer between the dogs body and the surface underneath, keeping the dog warm even in colder temperatures.

- The metacarpal/metatarsal pad has a heart shape and is located in the middle of a paw. While the metacarpal pad is on the front foot, the metatarsal pad is on the rear one. They are both shock-absorbing and load-bearing parts of the paw. Their function is overall very similar to the purpose of digital pads.

- A Carpal pad is the furthest part of a paw from claws and can be mainly found on the forelimb, yet some dogs may have it on the rear feet as well. Their structure is similar to the metacarpal pad. They often come in handy as they act like a dogs emergency brake. Suddenly stopping on a slope or a slippery terrain requires additional traction provided by carpal pads. However, the same applies if a dog chooses to stop quickly in tight spaces. Their structure also allows them to absorb shocks, and therefore protect joints when jumping. Lastly, the carpal pad helps a dog maintain control even at high speeds, acting as a means of achieving balance.

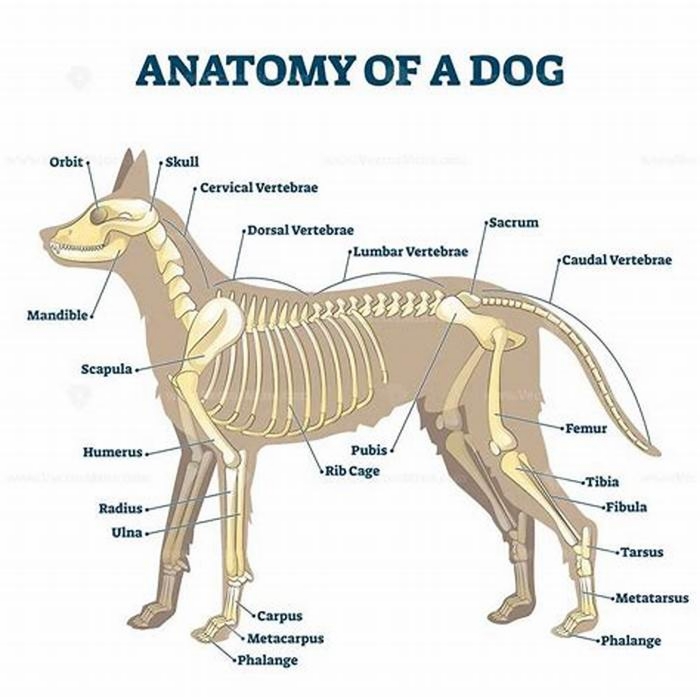

Bones

To understand how the canine paw functions at an even deeper level, lets take a look at its bones structure.

- Phalanges form the digits of the foot. There are three phalanges per toe, except for the first digit, the dewclaw. This could be compared to a human thumb and comprises of only two phalanges. The three phalanges are distal, middle, and proximal. The proximal phalanx is connected to the metacarpal/metatarsal bone to which well get in a minute. The middle phalanx lies between the proximal and distal ones. Finally, the claw is attached to the distal phalanx. Dogs have 4 toes per paw, excluding the dewclaws.

- Metacarpal/metatarsal bones connect to both phalanges and carpal/tarsal bones. As was the case of canine pads, metacarpal bones are present in the forelimb and metatarsal in the rear paw. As humans, our four-legged friends have 5 metacarpal bones. On the other hand, they, unlike us, have only 4 metatarsal bones.

- Carpal/tarsal bones are the equivalent of human wrist or ankle, respectively. They are 7 bones connected by various ligaments, creating a very firm surface that can withstand shocks. The whole joint is then called a carpus/tarsus. The bones are arranged into 3 irregular rows, with an accessory carpal bone being the fourth row.

Evolution

However, many years had passed before the canine paw developed into a well-known form. To search the origin of canine genealogy, we have to go back approximately 60 million years. Back then, a carnivorous mammal Miacis laid the foundation for the appearance of the modern dog. Nonetheless, you would be surprised to find out that Miacis looked like a weasel, was only as big as 30 cm (11.5 inches) and walked on its soles instead of toes. It has taken 25 million years of development to reach the next significant stage, the genus Leptocyon.

This genus is considered the first canine, yet the mammal still resembled a fox rather than a dog. Leptocyon already used toes for walking, slowly moving towards characterizing the modern dog. Around 20 million years ago, Mesocyon came, bearing the resemblance of a basic dog and having a more developed brain. Thanks to an increased intelligence and memory span, members of the Mesocyon family developed a pack mentality as they know could remember their own. If youre now saying that these mammals seem to behave like wolves, you wouldnt be far from the truth. Mesocyon was indeed followed by the wolves just 5-7 million years ago. These already walked on hind toes.

It was only 33,000 years ago that humans started domesticating some members of wolf species. The process of selective breeding enabled us to breed dogs for specific tasks. However, it has taken its toll on dogs health as detrimental genetic mutations were passed along with desired physical or behavioral traits. Despite the early existence of different dog breeds, many others were created by selective breeding. This accounts for the vast differences between modern dog breeds.

As was already mentioned, Miacis walked on soles while the modern dog uses its hind toes. Why was this change necessary? Moreover, why does the canine paw have only 4 toes, unlike humans? These questions might deliver the most essential information of the day. However, they may randomly pop into your mind, bug you before falling asleep or simply come in handy when a family conversation stalls.

Humans have five relatively long fingers to grasp and manipulate objects. Dogs, on the other hand, predominantly need their palms and feet for walking or running. Cursorial animals which need to maintain high speeds for long distances developed long limbs but shortened digits and fewer toes. Long limbs allow dogs to run speedily. When humans run, they roll their feet from heel to their toes. This process is lengthy, and thus, Leptocyon had already been using for running only its toes.

Lastly, the reason why dogs have only 4 toes is probably to lose excessive weight slowing the dog down. While the additional weight from having 5 toes is not that big, it can make a difference in such a small animal, especially over a prolonged period of running. On the other hand, the evolution of canine species introduced the dewclaw, a fifth digit providing an emergency break.

So, after all, the canine paw evolution is all about making the energy distribution during running more efficient!

Foot Bones

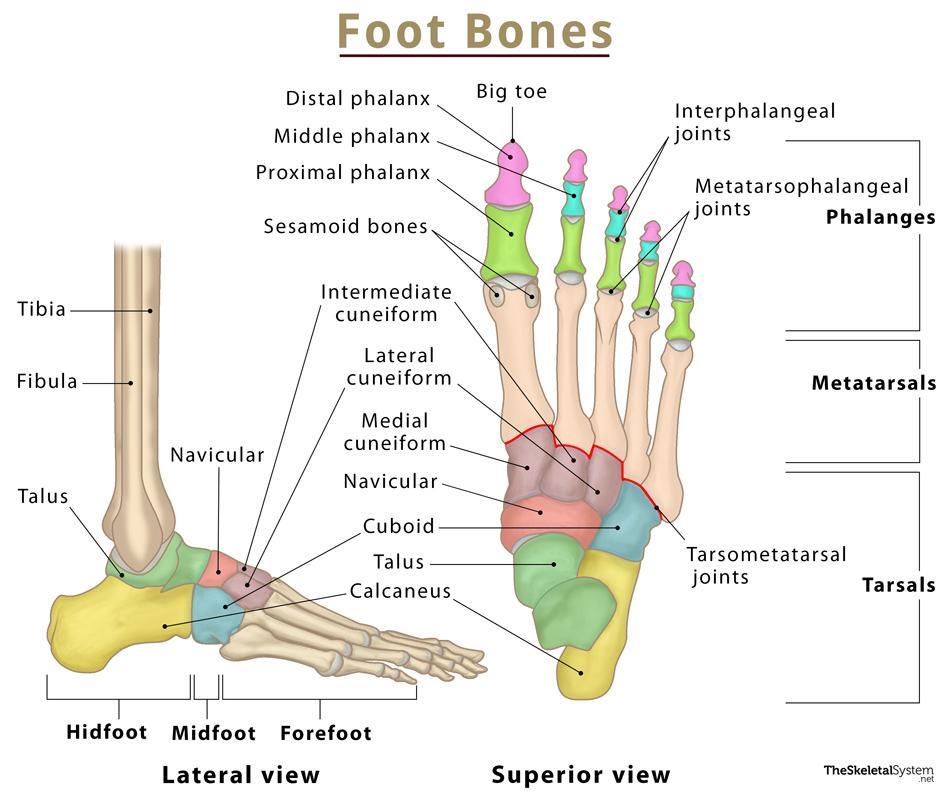

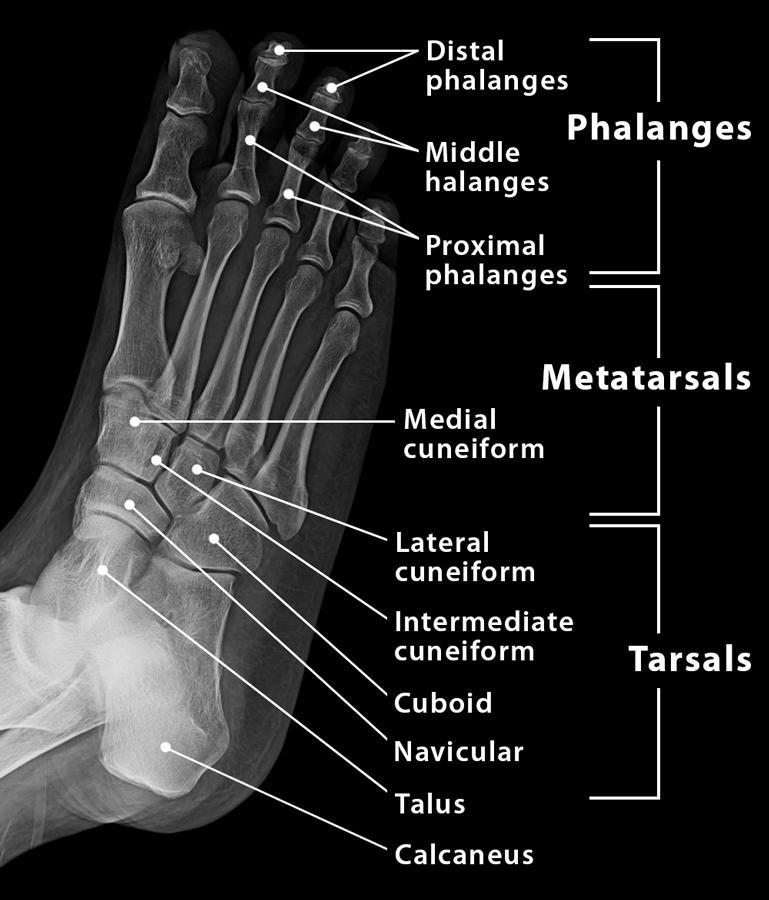

Humans have 26 bones in each foot that are classified into three groups tarsals, metatarsals, and phalanges. These bones give structure to the foot and allow for all foot movements like flexing the toes and ankle, walking, and running.

The foot can be divided into three regions, the hindfoot, midfoot, and forefoot.

Names of the Bones in the Foot With Basic Anatomy

Tarsal Bones

The tarsals are a group of 7 irregular bones forming the hindfoot and the midfoot. These bones are arranged in two rows, proximal and distal. The bones in the proximal row form the hindfoot, while those in the distal row from the midfoot.

Hindfoot

- Talus

- Calcaneus

The talus connects the foot to the rest of the leg and body through articulations with the tibia and fibula, the two long bones in the lower leg.

Midfoot

- Navicular

- Cuboid

- Medial cuneiform

- Intermediate cuneiform

- Lateral cuneiform

Some people may be born with an extra navicular bone (accessory navicular) beside the regular navicular bone, on the inside of the foot. This is a normal anatomical variation seen in around 2.5% of the entire population of the US.

Metatarsal Bones

These are a group of 5 long bones located towards the front of the foot, below the toes. These form the forefoot, along with the phalanges or toe bones.

These get shorter as we move from the big toe (hallux) towards the little toe and are numbered in that order.

Each of these bones has a head, body, and base. The base on their proximal side articulates with the carpal bones, while the head on the distal side articulates with the phalanges.

Also known as toe bones, these are the 14 long bones in the toes on each foot. As mentioned above, these form the forefoot with the metatarsals.

The second to fifth toes have 3 phalanges each, while only 2 are located in the big toe. These bones are named the proximal (closest to the ankle), middle and distal phalanges (farthest from the ankles) based on their location in the toes. The big toe only has the proximal and distal phalanx.

Being long bones, these are also anatomically divided into a head, body, and base.

There are two small ball-shaped sesamoid bones at the base of the big toe, near the joint between the 1st metatarsal and the proximal phalanx of the big toe. These bones act as the attachment point for multiple tendons and help with the movement of the big toe.

Joints Formed by the Foot Bones

In the Hindfoot

- Ankle joint: Synovial joint between talus, tibia, and fibula

- Subtalar joint: Between the talus and calcaneus

In the Midfoot

- Talonavicular: Between the talus and navicular bones

- Calcaneocuboid: Between the calcaneus and cuboid

- Intercunneiform: Among the three cuneiforms

- Tarsometatarsal (TMT): Between the distal tarsal bones and the base on the metatarsals

In the Forefoot

- Metatarsophalangeal (MTP): Between the head of the metatarsals and the base of the proximal phalanges.

- Interphalangeal joints: Between the phalanges on each toe. The big toe has only 1 interphalangeal joint, while the rest of the toes have 2 each.

Muscles, Ligaments, and Tendons

Many muscles, ligaments, and tendons are attached to the foot, which helps with all the small and large movements. The most important attachments are mentioned below.

Muscles

- Peroneal

- Anterior tibialis

- Posterior tibialis

- Extensors

- Flexors

Tendons and Ligaments

- Achilles tendon

- Plantar fascia

- Plantar calcaneonavicular ligament

- Calcaneocuboid ligament

Fracture of the Metatarsus and Metacarpus in Dogs

The metatarsal bones are the long bones in the hind foot (the arch of the human foot) that connect the toes to the bones of the ankle (tarsus). The metacarpal bones are the long bones in the front foot (the human palm) that connects the fingers to the bones of the wrist (carpus). Fractures of these bones usually occur as the result of major trauma.

These fractures can be classified as open (bones exposed) or closed, and can be simple or comminuted (multiple fragments). Depending on the nature of the fractures and the age of the animal, different methods of repair may be indicated for each situation.

Metatarsal and metacarpal fractures generally heal well without long-term effects on the cat, but they can lead to abnormal function of the foot if not properly treated.

What to Watch For

Symptoms of fractured metatarsus and/or metacarpus in dogs may include:

- Lameness

- Swelling of paw

- Pet not putting weight on the paw

- Pain when paw is handled

A thorough physical examination is important to determine if fractures are present and to determine if there are other injuries. No laboratory tests are required to make the diagnosis, but your veterinarian may recommend the following:

- Complete orthopedic examination

- Radiographs of the affected foot

- Chest radiographs to determine other injuries

Emergency care for concurrent problems caused by the trauma is the most important part of treatment. After stabilization, additional treatment may include:

- Cast or splint. Certain fractures of the metatarsal and metacarpal bones can be managed successfully with a cast or splint.

- Surgery. For some fractures, anesthesia and surgical stabilization of the bone fragments may be recommended.

- Pain medication. Injectable analgesics (pain medications) are given to the animal while being treated in the hospital and may be continued orally once discharged from the hospital.

Home Care and Prevention

After surgical repair or immobilization in a cast or splint, the cat will require restricted activity for several weeks and the cast or splint will need to be kept clean and dry.

A recheck appointment with the veterinarian will occur in several weeks to evaluate how the bones are healing (with new radiographs), to monitor the animals progress, and to make sure it is safe to increase the cats activity level.

Most metatarsal and metacarpal fractures are caused by trauma and since many traumatic events are true accidents, they are often unavoidable. Keeping your dog confined to a fenced in area or leash walk only can help prevent some traumatic events.

In dogs, there are four metatarsal bones in each hind foot and five metacarpal bones in each front foot. In the front foot, the dewclaw is a rudimentary thumb that has a metacarpal bone associated with it, but it does not reach the ground and has no function. The other four metacarpal bones and all of the metatarsal bones run parallel to each other and commonly more than one of the bones in the foot will fracture at the same time.

The middle two toes on each foot are considered the weight bearing digits because they support most of the weight. The outer two toes on each foot bear less weight and are considered the non-weight bearing digits. Fractures that involve only the non-weight bearing digits tend to cause less lameness for the animal than those that involve the weight bearing digits.

Fractures of the metatarsals and metacarpals can be classified as open or closed depending on whether the skin surface has been damaged during the injury. Open fractures have a greater chance of getting infected and may have more complications than closed fractures. Open fractures of the feet are common as there is little soft-tissue covering these bones.

As with all fractures, fractures of the bones of the feet can also be classified as simple, if each bone breaks into two pieces, or comminuted, if there are multiple pieces.

Each case of metatarsal and metacarpal fracture needs to be evaluated in its entirety (age of animal, severity of the fracture, experience of the surgeon, and financial concerns of the owner) to determine the most appropriate and best form of treatment.

Inappropriate case management, inadequate surgical stabilization, or poor aftercare can lead to complications such as non-unions (fractures that will not heal), malunions (fractures that heal in an abnormal direction or orientation), osteomyelitis (bone infection), or a non-functional foot.

In-depth Information on Diagnosis

A thorough physical examination is very important to make sure your dog is not showing signs of hypovolemic shock secondary to the trauma or blood loss. It is also important to make certain that there are no other injuries present. Additional tests may include:

- Thoracic radiographs (Chest X-rays). Chest trauma, in the form of pulmonary contusions (bruising) or pneumothorax (collapsed lung lobes secondary to free air within the chest cavity), must be ruled-out with chest radiographs prior to anesthesia to repair the leg.

- Complete orthopedic examination. A complete orthopedic examination must be performed to look for the cause of the non-weight bearing lameness as well as possible injuries in other bones or joints. Examination involves palpation of all of the bones and joints of each leg for signs of pain or abnormal motion within a bone or joint as well as an assessment of the neurological status of each leg. The thorough orthopedic examination is especially important for an animal that is unable or unwilling to get up and move on the other three legs. Specific palpation of the foot and finding swelling, bruising, pain, and crepitation (abnormal crunchy feeling with motion) can be highly suggestive of fractures of the metatarsal or metacarpal bones.

- Radiographs of the foot. Two radiographic view of the animals foot are used to confirm the diagnosis of metatarsal or metacarpal fractures. Based on the location and severity of the fracture, a more informed discussion with the owner can occur regarding potential treatments, prognosis and costs.

- No laboratory tests are required to make the diagnosis.

In-depth Information on Treatment

Emergency care for concurrent problems is paramount. Shock is a frequent result of major trauma and must be treated quickly. Treatment for shock involves intravenous fluid administration to maintain blood pressure and adequate oxygen delivery to the body. Injury to the lungs and chest cavity are also commonly seen after major trauma and may require supplemental oxygenation or removal of free air (pneumothorax) from around the lungs. Once stabilized, additional treatment may include:

- Soft-tissue injuries must be addressed in order to minimize the chance for the development of wound infections. Lacerations and other open wounds or open fractures must be cleaned of debris and covered or closed to minimize infections.

- In the interim between treating the emergency patient and stabilization of the metatarsal or metacarpal fractures, all of the orthopedic injuries that have been found should be addressed with splints and/or pain medications to keep the animal comfortable.

- Depending on which bones are fractured, how many bones are fractured, and the age of the animal, metatarsal and metacarpal fractures may be repaired in a few different ways. If at least one of the weight bearing bones is not fractured, the foot may be treated without surgery by immobilizing the foot in a cast or splint. The remaining unbroken bones act as internal splints that help to maintain alignment of the fractured bones. For those fractures that involve both of the weight bearing bones and especially those that involve all four bones in the foot, surgical stabilization will likely be recommended. Depending on the size of the animals bones, pins alone, pins and wires, or bone plates and screws can be used to provide stability to the bone fragments while they heal. After surgical repair, the foot is usually placed in a splint to protect the small implants while the bones regain strength.

- Fractures of these bones in the feet, as well as any other traumatic injuries that the animal might have, are painful and the dog will be given analgesics before and after surgery.

After discharge from the hospital, the animal must be restricted from activity to allow the fracture time to heal properly. Activity must be restricted for several weeks after surgery; the duration will vary depending on the severity of the injury and any concurrent injuries the animal may have. Restricted activity means that the animal should be kept confined to a carrier, crate, or small room whenever he cannot be supervised. Playing and rough-housing should be avoided, even if he appears to be feeling well. The use of stairs should be limited, and outdoor walks should be just long enough for the dog to relieve himself and then should be returned indoors for more rest.

The cast or splint must be monitored closely during the recovery period. If it becomes wet or soiled, it should be removed and replaced with new materials. The end of the foot should be covered with a plastic bag when the dog is taken outside to keep it from becoming wet. When brought back indoors, the bag must be removed. The toes that may be visible at the tip of the bandage should be watched for swelling, discharge or odor. If the dog begins chewing at the cast or splint, there might be a problem that should be checked by the veterinarian. Generally, the veterinarian will want to check or change the bandage materials regularly to make sure that there are no hidden problems and that the dog is progressing well.

Analgesics (pain medications), such as butorphanol (Torbugesic), or anti-inflammatories, such as deracoxib, aspirin or carprofen (Rimadyl), should be given as directed by the veterinarian.

If surgery was performed, there will be a skin incision that will be concealed by the bandage. Your veterinarian will check the incision and remove any sutures at one of the follow-up appointments.

If at any point prior to the recheck radiographs being taken the dog stops using the leg again after some improvement following surgery, there could be a problem.

Several weeks after surgery, the foot will need to be radiographed again to make sure the bones are healing properly. If the healing has occurred as expected, the cast or splint may be replaced with a less supportive soft-padded bandage, or may be left off altogether, and the dogs activity level will be allowed to increase slowly back up to normal over the next few weeks.

In general, any implants that were used in the repair will be left in place unless they cause the animal a problem at some point in the future. Potential problems can include migration (movement) or infection of the implants.